THE FIRST FOLIO

Intentional errors point to clues

in the world’s most expensive printed text book.

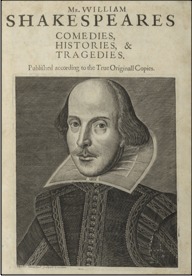

Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, published in 1623, is usually referred to as the First Folio because of the large ‘folio’ format in which it was printed. A collection of 36 of the Bard’s plays, half of which had never previously been published, it is universally regarded as one of the most influential books ever. A copy auctioned at Sotheby’s in 2020 sold for $10 million, making it the most expensive printed text book in the world.

Interestingly many scholars have suggested it’d be worth a lot more if it wasn’t such a botched print job. There are 24 wrong page numbers and countless glaring mistakes which researchers insist are all just printing errors.

But amazingly, in almost 400 years, no-one seems to have bothered to ask why all those numbers are ‘wrong’. There was no such thing as mass production during the Renaissance. Each folio leaf (two printed pages per side) was peeled off the press and assembled individually, by hand, along with hundreds of others, until they grew into one gigantic book. Any wrong page number should have been spotted and corrected on the next pass through yet all 235 known surviving copies today have exactly the same wrong page numbers. Clearly these ‘mistakes’ were intentional. But why?

Shakespeare used wrong page numbers to indicate where he hid clues and secret truths.

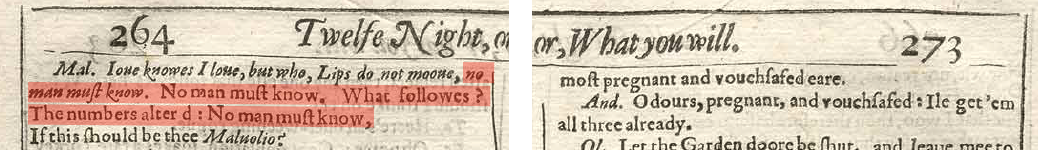

Nineteen years’ intense research has convinced Green they are all part of an elaborate code to lead us through the puzzle he’s created for us. In fact the poet/playwright clearly tells us so in one of his most popular plays, Twelfth Night. In one scene the character, Malvolio, is reading a letter that has been left conspicuously in his path to play a trick on him. At the top of Page 264 in the First Folio he reads from the letter: “No man must know. No man must know. What follows? THE NUMBERS ALTERED: No man must know.” And sure enough if we look across to the next page in the Folio we see it is ‘altered’… Page 273.

The clue to what’s going on with the wrong page numbers could hardly be any clearer because as the scene continues we find Malvolio trying to solve a code. He reads aloud, “MOAI… If this fall into thy hand, REVOLVE.” The code is never solved within the play itself but it turns out to be the very KEY to solving a far bigger code the author has embedded across all his Plays and Sonnets for future generations to discover!

He’s playing a brilliantly conceived game with us, engineered down to the minutest detail throughout the decades of his entire career… truly a ‘Code within a Code’!