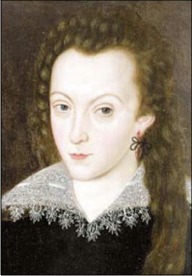

Henry Wriothesley

A 'Rose' by any other name?

The official story is that Henry Wriothesley (some pronounce it “Rizzley” – others “Rose-ly”), 3rd Earl of Southampton succeeded to his father’s earldom in 1581 and became a ward of court under the care of Lord Burghley (William Cecil). It seems he was in good company because the young Francis Bacon, though brought up in the home of Nicholas Bacon and his wife, Lady Anne (Queen Elizabeth’s sister), was also kept under close scrutiny by the Queen’s chief advisor and Secretary of State, William Cecil.

For good measure ‘ward of court’ had also been the fate of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. So if the Prince Tudor theories are correct it would seem the Queen had a habit of making sure her unacknowledged children were close by under her and Cecil’s watchful gaze. Besides having the best private tutors available in Cecil’s household, Wriothesley was later educated at Cambridge University and at Gray’s Inn, London (as were both de Vere and Bacon). At age 17 he was being powerfully urged by Cecil to marry Oxford’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth Vere… Cecil’s grand-daughter. Had this plot gone through (and if indeed Wriothesley was an anonymous heir to the Tudor throne) it would have very conveniently paved the way for the Cecil family to eventually occupy the ranks of royalty. (O, what a tangled web!)

It is curious then that the first 17 sonnets are universally recognized as a complete set called the ‘Procreation’ sonnets, all urging the fair youth to produce an heir so that his beauty shall not die with him. But Wriothesley was having none of it and Cecil fined him an astronomical sum for thwarting his objectives.

It’s partly on account of such jockeying for position at court that Wriothesley is assumed, by Stratfordians, to have been Shakespeare’s patron. The theory is boosted also by the fact that the epic poems Venus and Adonis (1593) and The Rape of Lucrece (1594) were both dedicated to the young Henry. There is, however, no evidence at all that the man from Stratford ever crossed paths with Southampton. Moreover, the fatherly tone of the Sonnets and the way in which the author lectures his so-called ‘patron’ on morals would have been utterly unthinkable for a commoner addressing an Earl! He would’ve been hauled before the Star Chamber and forced to recant his presumptuous statements. But nothing of the sort ever happened.

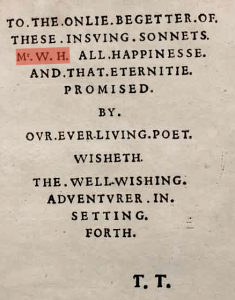

It’s almost wholly recognized today, even by Stratfordians, that Wriothesley is the so-called Fair Youth of the Sonnets and that the dedication is addressed to him, albeit in a curiously cryptic way (“Mr. W. H.”).

On February 19, 1601, Wriothesley was found guilty of treason for his part in the Essex Rebellion. Robert Devereux, the 2nd Earl of Essex, and four other co-conspirators, were summarily beheaded. Wriothesley was condemned to death but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment through the intervention of Sir Robert Cecil, the then late William Cecil’s son. This might seem at first to have been merciful and gracious of Cecil but, if the Prince Tudor scenario is true, it was more likely a stroke of pure genius.

Wriothesley was stripped of his titles and confined to the Tower indefinitely, but under permanent threat of execution. It seems reasonable to construe that the cryptic Sonnets Dedication is revealing him to be the dedicatee, but now as plain “Mr. Wriothesley, Henry”.

From Cecil’s point of view what better way to control the situation and extract total co-operation from other ‘players’ in this web of royal conspiracies (especially if Oxford really was Henry’s father) than to hold the youth hostage under permanent threat of death, subject at any moment to Cecil’s whim? Elizabeth was already rumored to be going senile. Would she have had the will or the power to stop Cecil from enacting such a threat? She had already signed the death warrant for Essex who was (you may have already guessed?) yet another suspected anonymous son!

Upon Elizabeth’s death, as soon as the succession to the throne was secure and the Tudor dynasty was irrevocably ended, the first official act of the new King James was to issue a full pardon and release Wriothesley from the Tower. He was made a Knight of the Garter and captain of the Isle of Wight and was restored to the peerage by an act of Parliament. In 1603 he entertained Queen Anne with a performance of Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost (oh, the irony!) by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, soon to be known as the King’s Men.

Of course, all the above will be regarded as rank speculation and that’s perfectly understandable for there is no solid, slam-dunk, written-in-blood, proof! Or is there?

THE GAME‘s afoot!